The first One Hundred Days of Uncle Joe have gone by in a whoosh and we’ve mostly forgotten the guy with the Art Deco hair. Time rushes on. I look at the unread novels on my bookshelf and wonder what crime I need to commit to get sentenced to prison long enough to read them all. Probably handing over nuclear secrets to the Russians but I assume they already have them.

Crime, however, seems unlikely due to the fear of virus transmission which has locked us in our homes and brought me under close supervision by my wife. Thanks to her, my consumption of double cheeseburgers is at an all-time low; my intake of greens is now close to that of an adult giraffe. I am in her hands even when I’m not in her arms. She keeps telling me, “There is no point in wasting money,” and so we live like tenant farmers in the Dust Bowl, we save tiny portions of leftover salad in little plastic containers and we use bars of soap until they are the size of a potato chip. I grew up with Frugal Monetary Theory, but I’ve been corrupted by the ATM: stick in a card and it blows money at you like bubbles from a pipe. She finds a wad of cash in my jeans pocket and says, “What do you need all this money for?” Good question.

I’m a happy man. I had a happy frugal childhood, riding my bike around the countryside back before cellphones and apps that parents could track you with on a laptop, but I avoid talking about happiness because I have young leftist friends who, if I admit to being happy, say, “Well, that’s very nice for you but not everyone is as privileged as you were.”

Privilege was not what made me happy. Dad worked for the post office, we were six kids, so though we weren’t impoverished, we could see it from there. No, it was the bike and freedom and the truck farmers who’d pay a kid to hoe corn and pick strawberries and I’d take my dough to the corner store and buy a couple Pearson’s Salted Nut Rolls and take them down to the Mississippi and eat them and skip stones. It wasn’t about privilege. Why can’t a man talk about happiness without getting a poke in the eye from someone who’s just read a book about systemic inequity and wants you to know it?

The great privilege of my childhood was hoeing and weeding, which is denied to kids now whose moms go to Whole Foods to purchase raspberries from New Zealand and a bag of baby arugula hand-raised in the coastal foothills of Northern California by liberal arts graduates, instead of growing food in a garden and affording their children a useful education.

Weeding is editing and editing is a basic skill desperately needed now that the computer has led to floods, downpours, typhoons of verbiage. Everything is ten times too long. (I had a couple thousand words here about my old editor William Shawn, which I’ve taken out, as you can see.) I read a memoir now and then and I think, “This person never mowed a lawn or weeded a flower bed.” Their book has, in a manner of speaking, a lot of old rusted cars and busted appliances sitting in tall weeds that need to be thrown down in a coulee and the grass mowed.

I grew up mowing lawns, parallel lines, back and forth, it was deeply instilled in me and that’s why I write prose today and not

Butterflies go tipitipitipitipi

toward the blue

crocus and focus

looking for nectar

and stick out their

connector like a straw

and cry,

aha

Notice how the irregularity makes it seem sort of artistic. So what? Sew buttons on your underwear. I am happy going back and forth, back and forth, putting subject and predicate together. It’s therapeutic. When I was your age, kiddo, I had artistic ambition, which was the privilege of ignorance — to look down the road and imagine being honored by the U.S. Essay Association, but in the pandemic, it’s all about today. A walk in the park, a skinny sandwich for lunch, a brief nap, a poem.

A virus called COVID-19

Can be sneaky, mysterious, mean,

But once immunized

I have been surprised

By days that are calm and serene

And limericks that are pleasant though clean.

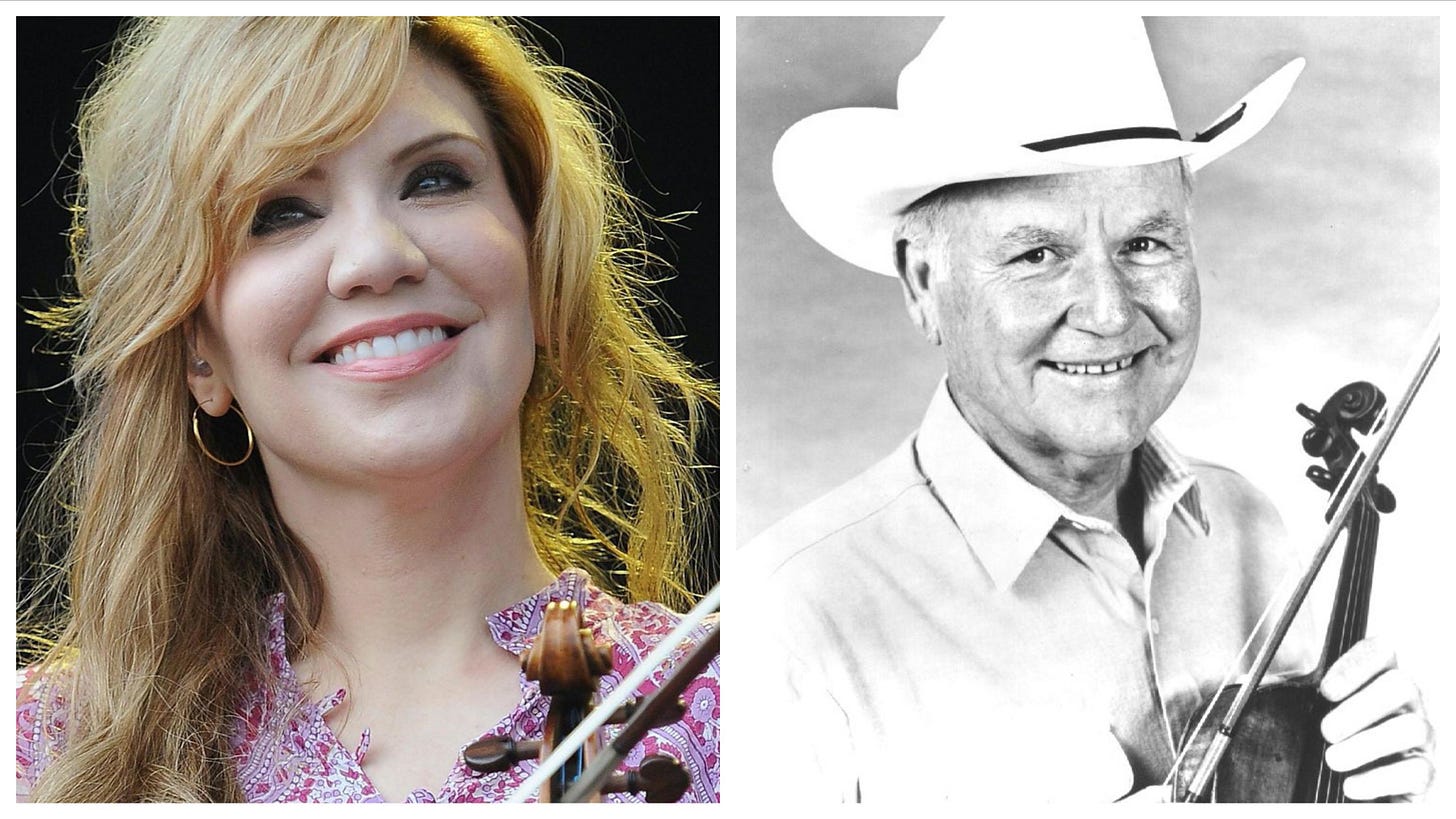

Join us when the link goes live on Facebook this week at 5:00PM CT where we feature a broadcast from the Ryman Auditorium in Nashville, May 1, 2004. Featured guests: Johnny Gimble and Peter Ostroushko, Kacey Jones, Buddy Emmons and a special appearance by Alison Krauss.

Feel free to comment on this post by clicking on the comment icon that is below the title or email us at admin@garrisonkeillor.com

I identify with your interpretation of Privilege and I concur. Success in life has eluded me to my personal satisfaction but is viewed by others as a life well lived

As Mr Jagger sang, "you cant ALWAYS get what you want"

But if you try sometimes...... you get what you need".

"someone who's just read a book about systemic inequity" - Boy, did that strike home! One of my "failings" is probably that I frequently get overly analytical about life as it goes on around me! Sometimes, though, GK and Friends can broaden my interactive prospective, at least a little. A case in point is the time, a year or two ago, that The Writer's Almanac alerted me to a coming performance by Harry Belafonte. I went, expecting a lot of "Day-O, Day-O" and Caribbean music. Instead, Harry talked about his mother, while he was growing up poor in a Northern city. He introduced us, his largely white, middle-class audience, to the warmth, the neighborliness, and the mutual support provided by those around him. Listening to him, it occurred to me that he had grown up with a marvelous sense of social support and inclusion.

Could it be, despite all those sociological books and such, that those of us in the "Keep off the Grass" suburbs, are the ones suffering from "inequity"? How many of us seldom know the folks even two blocks away? We expect each family unit to be autonomous. To even consider that our neighbors might need assistance would seem an affront to "The American Dream." Could it be that, like natural ecology, each layer of social ecology has its advantages, as well as it's vulnerabilities? It seems to me that as a society, we put too much emphasis on the $ sign, and what having more wealth can provide. Basic needs need to be met, yes. But if, sometimes, the neighbor sees you're "in a pinch" just now, and gives needed help, you might return that caring attention in some way to them along the way. "True wealth" could be counted in part as the strands of interpersonal relationships that we've developed and can count upon when financial funds fail. What may seem like straightforward systemic inequity might overlook the richness of the adaptations folks make when financial resources seem too scarce. I saw a "joke" graph once in "The Journal of Irreproducible Results" - how to fix poverty. Just add money." Harry Bellefonte and his mother would say "Life's a lot more complex than that!"